The island was formerly known as MÁKRI or DOLÍCHI (because of its long shape), ICTHYÓESSA (because of its many fish) and ANEMÓESSA (because of its strong winds). From the historic age, it was given the name “Ikaría” from Íkaros, who drowned in its waters. Μythical Íkaros, with his father Daídalos, were attempting to escape from Mínoas in Crete, by flying with wings that were made and attached to the body. Daídalos headed west to Sicily and Íkaros headed north. He was so enchanted by the view that he didn’t hear his father’s warnings, and he soared so high that the sun melted his wings that were glued together with wax.

The island has been inhabited from at least the Neolithic Age (7000-2800BC) according to settlement findings. Iones established themselves here, after the Trojan War, and assimilated the Pelasgian (pre-historic Greeks) population. In the 8th century BC Ionian colonisers came over from Mílito in Asia Minor. After the Persian wars (5th century BC) when it was conquered by them, the island became a member of the Athenian Allies, and proved to be, along with Sámos, among the most faithful supporters.

During the Hellenistic years, the now-deserted Tower of Drákanos was built, which was used as a lighthouse during a later period. The island was used, as were many others, as a place of exile during Roman rule. It continued as a place of exile during the Byzantine and for a long period (from 3rd – 13th centuries AD) the island first suffered from the plague of raids by the Huns and Goths and later from forays by pirates from various countries. Ikaría, as many other Aegean islands, met with hard years that ravaged the island. One indication of the situation has been handed down to us by the Florentine priest Christoforo Buodelmonti, who visited the Aegean during this period. He wrote that there were no men, on most of the islands, and that the remaining inhabitants were “like cattle” (article written by the historian Ioánnis Melás, “Seven Days” magazine from “Kathimeriní” newspaper, 21st July 1998).

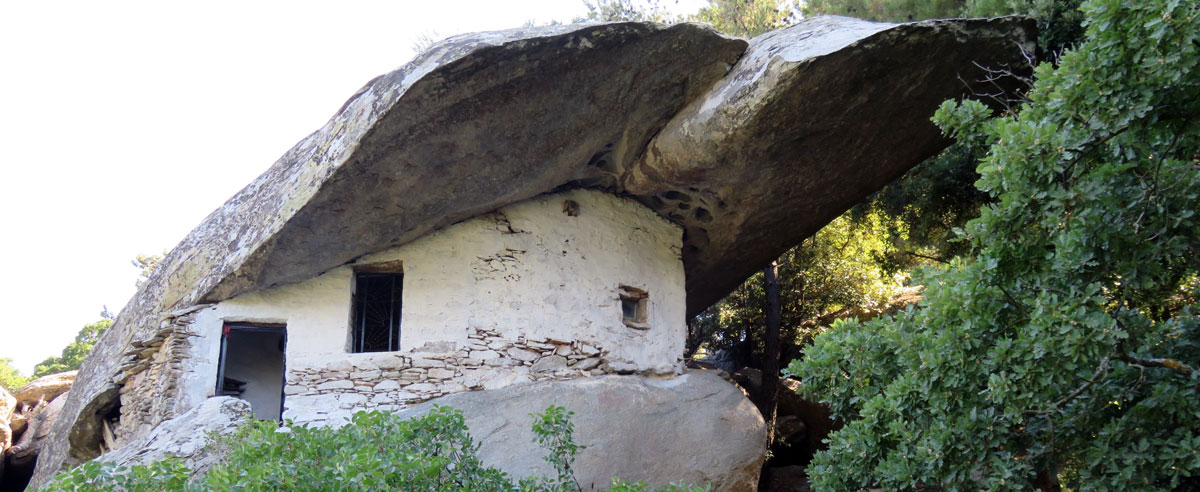

After the fall of Constantinople to the Franks, the island was conquered by the Venetians, who were then succeeded by the Turks. Actually after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks (15th century), the rich folk of Ikaría migrated to the Venetian N. Chíos (as did the Sámians) and other areas of the Mediterranean, while the poorer folk took to the mountains and started their new lives in caves. They lived and worked during the night and during daylight they hid themselves away, so as to give the impression of a deserted island. In this manner they did not kow-tow to the Turks. They started to live normally, during daylight hours, around the end of the 16th century, when the Sultan assured them that they would be left unharmed.

During the 4 years of the Russian – Turkish war (1770-4), the island was ruled by the Russians. At the end of the 18th century the Turks retract their former promises and place heavy taxes on the islanders, which they refuse to fulfil, without thinking of the consequences of such a deed. This action was quite incredible; taking into account the terror that reigned during Turkish rule and the exemplary punishment the Sultan enforced. The island joined the National Uprising against the Turks (1821) from the beginning and offered every form of assistance (the Turk Aga was deported to Krini-Tsesme in Asia Minor, along with his fellow countrymen). Unfortunately the London Protocol (1830 – England-France-Russia), in which the Greek Nation was to be re-established, decided to send the island back to slavery. Fortunately, in its new condition, the island established self-government together with the islands of Pátmos, Léros and Kálymnos, with the obligation of paying taxes to Turkey. When in 1912 there began rumours of Turkey sending over Kurdish settlers, the islanders revolted and formed the “Eléftheri Ikariakí Politeía” (Free State of Íkaros). This action was felt throughout the world. In the November of 1912 with the Balkan Wars, the island reunited with Mother Greece.

In the mountainous region of Rachón, the Íkarian dialect has many elements of the ancient Greek language, which indicates the continual Hellenic population throughout the years.

The houses of the village Christós in Ráches are scattered and quite a distance from the centre. Because of this, the villagers first finish their work in the fields and end up coming to shop at night. In order to serve them the shop-owners open up at night and for most of the daytime remain closed.

The Ikarians are very fond of celebrations. Boiled meat with gravy or meat in red sauce with rice, bread and wine is served at all the feasts (the meat is goat’s meat and usually wild, known as “raská” by the locals). After the food comes the party with music, dancing and singing. There are many feasts, some of which are: Ag. Marína (Aréthousa) on the 17th July, Profítis Ilías (Ag. Kírykos, Évdilos) on the 20th July, Ag. Paraskevís (Karkinágri) on the 26th July, Metamórphosis toy Sotíros (Christós) on the 6th August, Panagía (Gialiskári, Christós) on the 15th August and Ag. Sophía on the 17th September in Monokámpi. Also on the 17th July, the anniversary of the liberation from the Turks, there are festivities throughout the island and from 1990 onwards, the “Ikariáda”, for the air acrobatics, are re-enacted every 4 years in different parts of the world.

You should definitely visit Thermés, today’s Thérma, with its therapeutic springs (its citadel was close to toady’s village of Katafýgi), Oinói standing on the site of today’s village of Kámpos, which was a very prosperous town (remarkable findings on exhibit in the local Museum), Drákanon (ruins) town that stood on the eastern side of the island (ruins of its citadel still remain, as well as ruins of the harbour. On the citadel is the Hellenistic three-storey tower (3rd century BC), which still stands today and is conspicuous) and Nas, with its ruins of the temple dedicated to goddess Ártemis. In the area of Kámpos are the manor houses of the exiled Byzantines.

Certainly you must taste “raskó” meat (wild goat), “katsikísio pastourmá” (cured goat meat) and “touloumotýri” (white cheese preserved in goatskin) as well as the local wine (fokianó). Among the island’s fruits, the “kaïsia” (apricot), with its stone as sweet as an almond, stands out.